What’s the one landscape you would want to avoid after dark?

Perhaps you think there is nothing scarier than a city after hours, or a country graveyard, or the subzero temperatures of a tundra. The dark can take beautiful views and turn them into treacherous labyrinths. None more so than bogs. As a child of the 80s/90s, I shared in the genuine fear of bogs, marshes, and quicksand which defined stories and films of this period. One story which particularly sticks with me is Littlenose and the Great Elk, where the protagonist gets lost in an unfamiliar boggy landscape after dark. Frightening!

So, when I stumbled across the story of the Amcotts Moor Woman, a bog body from c.300 AD, in October of 2021, my curiosity was naturally piqued. I had lived in the Isle of Axholme and had ancestors there, but I’d never come across her story. I was in need of an idea for a new book – NaNoWriMo being the following month – and I’d failed to find anything which really sparked for me. Until I found her.

Thank goodness I didn’t actually find her, like poor John Tate who unwittingly stabbed his peat-cutter through her in 1747. Nowadays, peat cutting is still done close to where I live, and I can tell you: those tools are heavy and indiscriminate in their duty. I can only imagine how Mr Tate felt to find his winter fuel (peats need to dry for a while before they’re burnt) contained the remains of a person.

But she was a real mystery, and mysteries are what I love to write about.

Her discovery and the treatment of (most of!) her remains is well-documented, but there were questions to her story – both in life and in death – which remained unanswered. Not least amongst them was what happened to the parts of her which were dug up but were not re-buried or re-housed? The precision of the blade striking through her latchet also sparked an interest: could the simple strap have pulled the implement towards it, wanting to be found? And then there was the biggest questions of all: Who was she? and why was she there?

The gaps these questions opened up in two periods of history was exactly what I needed to allow the story to grow, and I realised it would have to be a dual timeline story, one part set when she lived and one part set when she was found.

Insular communities, like the Isle of Axholme during both points in history, do not take well to change. Especially change brought on by outsiders. I imagined, therefore, that Tate would initially lay his claim of guilt at the door of Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden. He was chiefly responsible for introducing draining methods to Lincolnshire, prompting big and violent protests against the 17th century engineer in the Isle, and it stood to reason that some of that residual prejudice had been handed down. I kid you not, some people in the Isle still had a mistrust of the Dutch while I lived there!

But Vermuyden and his team were not the first ones to drastically alter the landscape of the Isle. 1,500 years earlier, the Romans cut back the dense vegetation so that the native Britonscould not so easily conceal themselves. Nowadays, we know that the removal of trees causes flooding. Perhaps they did then, too, but they certainly didn’t care. And there’s another question: What was being hidden which was important enough that the Romans wanted to find it so desperately they altered the landscape?

Cue: the Amcotts Moor Woman herself. Whoever she was, she was almost certainly (judging by her attire) a local person. She would have lived and worked in the Amcotts area most of her life, and certainly been familiar with it. So how did she end up falling victim to it? Imagine again that boggy landscape in the dark. It was scary before, but now it’s changed: the trees have gone, the boggy pools have grown both in width and depth. What was your playground and your livelihood, is now your peril. And those things which the landscape had helped you conceal, are now laid bare.

One final feature: as a theologian, I couldn’t ignore the opportunity to explore the advent of Christianity within England. The “Plague of Conscience” which was being spread by the mysterious wandering monk, Amphibulas, was also causing a social stir. Christianity would grow to absorb many of the superstitions and beliefs of Pagan festivals but, in this Pre-Constantine era, Christianity was as alien to the Romans as any other non-institutional religion.

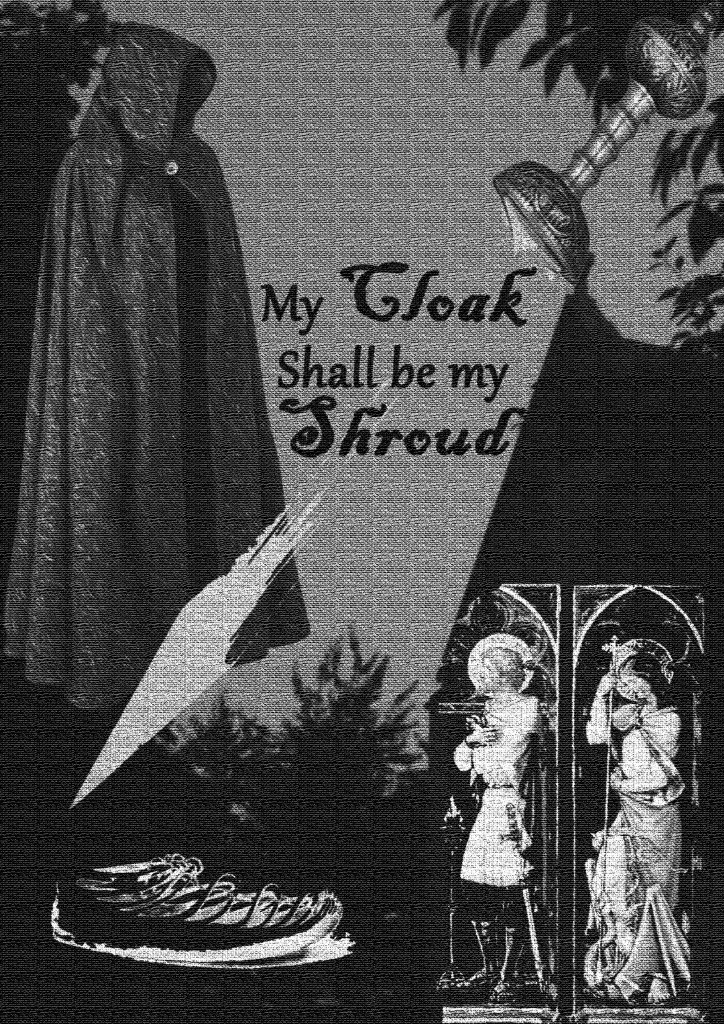

For the sake of my story – without giving away too many spoilers for when it is finally published(!) – the Amcotts Moor Woman was protecting something: something the Romans were very anxious to get. When she disappeared without trace, her people blamed her Silurian lover and the Romans in equal measure, cursing both to know no rest until the mythical cloak of Amphibulas is placed over the monk’s heart. The location of both things is hidden within a series of challenges established by the Amcotts Moor Woman’s people, all of which begin with her latchet. The latchet itself is a measure, the first part of the riddle which needs to be resolved. In full, the riddle runs:

What length is cut the mare’s tail from the lion’s castle there?

The servant of the King of Kings locks with the monarch’s hair.

Far cries the offered martyrs on their distant deaths to hide

The secret of the faceless man who slips from side to side.

To rid us of our worldly woe must heaven be made to pay?

And he who adds three more to him will light the pilgrim’s way.

For in the lion’s castle, its heart has lain the key

To draw aside the martyr’s mask and set his spirit free.

Cursed be the one who seeks this garment wove in smoke,

He dons the armour of the Lord, with righteousness his cloak.

By way of Caerleon, St Davids, St Albans, and Lincoln, all roads ultimately lead back to Amcotts, with the solving of her murder 1,500 years after it was committed.

Is it wrong to sow these seeds amongst the cracks in history? To take what is thin fact and mythologise a more rounded idea upon it? Absolutely not. After all, myths, legends, and folktales grow from a kernel of fact. This means they never lose that truth as they develop into taller tales. It is unlikely any further evidence will come to light concerning the Amcotts Moor Woman, but she deserves her story to be told, even if it is imagined.

And besides, who’s to say this was not the case..?

Words by VIRGINIA CROW

The Lincolnshire Folk Tales project is deeply grateful to Virginia for this post.

Virginia Crow is an award-winning Scottish author who grew up in Orkney, but has deep Lincolnshire connections. You can find out more about Virginia’s exploits by following her on Twitter/X: https://x.com/DaysDyingGlory

Her book, The Year We Lived (an award-winning historical adventure built upon the folklore and superstition of eastern England in the post-conquest period), can be purchased by clicking this link.

Leave a reply to Susan Crow Cancel reply