The Haxey Hood is a game, played annually on the twelfth day of Christmas. It involves a ‘lord’, a ‘fool’, eleven ‘boggins’ including a ‘chief boggin’ and anyone else who wants to join in. Their aim is to take the ‘hood’, a leather cylinder, to one of four pubs (three in Haxey and one in the neighbouring village of Westwoodside), without running with it, or throwing or kicking it, which means it ends up being transported in a big (and largely inebriated) scrum called the sway, which frequently breaks into folk songs, singing them as though they are football chants. The hood is then kept on display at the winning pub for the rest of the year. We have dropped this pin behind the church in Haxey, where people gather to hear the fool make a speech before the Haxey Hood game begins in the field to the west.

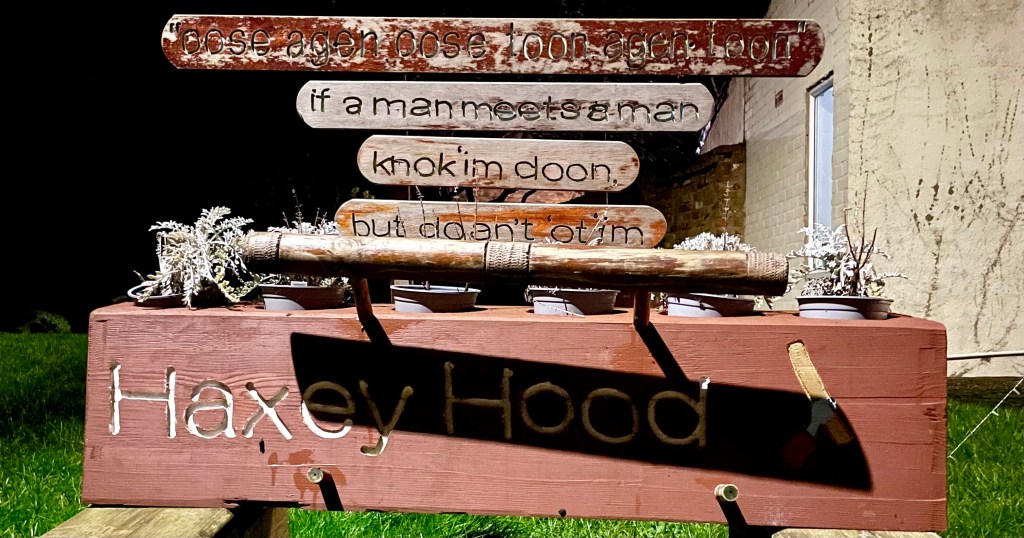

The only rules are pretty simple: don’t run with or throw the hood, and stop to pick people up when they inevitably fall over in a mass of what can be up to two hundred (almost exclusively male) bodies. The boggins help when that happens, and try to steer the sway away from danger and damage. The landlord or landlady of the winning pub must be passed the hood without stepping over the threshold, and must then give everyone a free drink. Such is the price of glory. A unique chant is bellowed by all at the end of the fool’s speech, before the game begins, and occasionally at other times: ‘Oose agen oose, toon agen toon, if a man meets a man knock ‘im doon, but doan’t ‘ot ‘im’, followed by a big cheer.

In the days leading up to the game, the boggins, lord and fool visit pubs in neighbouring villages, sing songs with whoever wants to join in, and collect money for local charities. This is repeated plentifully on the day of the Hood, which begins with breakfast in the four pubs from 9am. Use these links to hear Haxey Hood renditions of the three common songs of the Hood, recorded in 2024: ‘John Barleycorn’, ‘Drink Old England Dry’ (complete with the chant mentioned above), and ‘The Farmer’s Boy’. The Fool, smeared in coaldust to represent muck, is then smoked over damp straw outside Haxey church and makes his speech, usually at about 2.30pm, and the games begin soon after. The three songs are also sung throughout the game itself, emanating regularly from the steamy sway as it wobbles up the streets, often well into the night. The video below, which is somewhat less rowdy than the brilliant renditions above, was supplied by Anthony Cropper of West Stockwith, in his local pub The White Hart, on 4 January 2025, two days before the game.

Various legends exist to explain the origins of the Haxey Hood and its constituent features. Easily the most prominent is the story that Lady de Mowbray (the area was a stronghold of the Mowbrays in late medieval times) lost her riding hood to a gust of wind one twelfth night in the fourteenth century, and thirteen peasants then chased it through the fields. When they retrieved it, she called one a fool (because he had been too shy to hand it back himself), and another a lord (because he had not), and donated thirteen acres of land to the townsfolk on the condition they re-enacted the chase every year. If this is indeed the origin of the Haxey Hood, the game likely first took place in about the 1350s. However, as Jacqueline Simpson and Steve Roud note in A Dictionary of English Folklore, ‘none of this is likely to be historically accurate’. The official website can be found here.

There is a small permanent exhibition about the Haxey Hood, with some good historical artefacts, at North Lincolnshire Museum in Scunthorpe. Many books that are in print discuss the Haxey Hood, including Stephen Wade, The A-Z of Curious Lincolnshire (2011), and Lucy Wood, The Little Book of Lincolnshire (2016). Maureen Sutton, in A Lincolnshire Calendar (1997), includes an account of the Haxey Hood by William Andrews, published in 1891, when the smoking of the fool was a little different to what it is today: ‘The “Fool”, sitting in a loop formed in a stout rope, is suspended from one of the limbs of the tree, and is let down into the dense choking smoke again and again, to the infinite gratification of the rustics.’ In her book Lincolnshire Folklore (1936), Ethel H. Rudkin gives a long and luxurious account of the Haxey Hood in 1932. Little has changed – though David Clark, in It Happened in Lincolnshire (2016), gives a much more recent account, including an assessment of how the proceedings have been altered (very slightly) to accommodate modern sensibilities and health and safety concerns, and to include children. However, the roads don’t close, and anyone who either attempts to drive through the villages or who parks in their main streets on the afternoon or evening of 6 January is a different, bigger and less performative kind of fool than the one depicted in the photo at the top of this page.

The Haxey Hood is a grand and proud tradition. It has not suffered from overexposure in the way that some folk customs have, and is very much a living bit of folklore that means a great deal to people. Alex Harvey, in our anthology Lincolnshire Folk Tales Reimagined (Five Leaves, 2025), fictionalises its origins in five parts, beginning in early medieval times and ending with a rousing depiction of the game today.

Words and images by RORY WATERMAN

Leave a reply to The Stamford Bull-run – Lincolnshire Folk Tales Project Cancel reply