Large – sometimes impossibly large – phantom black dogs are a staple in English, and more generally western, folklore, and have been given many localised names. Throughout East Anglia (and sometimes in south-east Lincolnshire) they are generally referred to as Black Shuck, especially if they are said to shape-shift, or (more specifically in Lincolnshire) as Hairy Jack.

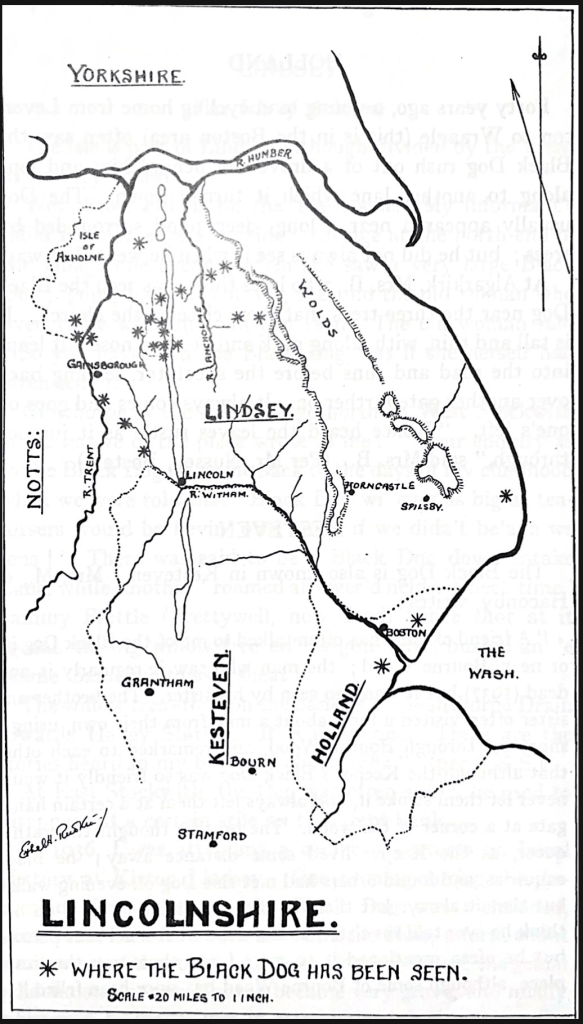

In most traditions, phantom dogs are usually sinister or malevolent, or even portents of impending death; in many Lincolnshire stories about them, however, they are harmless or even companionable. The folklorist Ethel Rudkin begins her essay ‘The Black Dog’, Folklore 49.2 (1938) by claiming ‘the Black Dog walks in Lincolnshire still’ and that ‘I have seen the Black Dog’, and she recites many anecdotes of sightings she claims to have collected – mostly of alleged appearances between the Lincoln Cliff and the River Trent in northern Lincolnshire, close to the rivers Till, Ancholme and Eau, but also from the coast and Fens, and coving all three of the county’s historic Parts. She notes that ‘He is certainly focussed on the river-systems of the Humber Estuary’ and that he is ‘a kindly beast’. Rudkin’s article is one of the most thorough accounts of black dog sightings in England, and when the Devon folklorist Theo Brown wrote her own article called ‘The Black Dog’ (Folklore, 1958), she referred to Rudkin’s ‘famous article’. For that reason, this pin has been placed outside Rudkin’s former house in Willoughton, which has quite recently acquired a blue plaque (and lost the Victorian gate-post on which it was initially placed), and which (perhaps unsurprisingly) is in a part of the county with a particularly high density of her reported sightings. Daniel Codd, in Haunted Lincolnshire (2007), discusses several alleged sightings – including one as recent as the year 2000 at Thornton Abbey near Grimsby – which are more sinister. Mabel Peacock, who lived most of her life just north of where Rudkin lived, also gave a more malevolent account of black dogs. Writing in the journal Folklore in 1901, she claimed that ‘black dogs with eyes glowing like hot embers, phantom calves, white rabbits, and other eerie animals, are sometimes said to haunt places where murder or suicide has been committed.’

Most black dog anecdotes, which are numerous, do not amount to folk tales. Rudkin’s essay quotes a ballad called ‘The Legend of the Ghost in Bonny Wells Lane’ by Muriel M. Andrew of Sturton-by-Stow, about a man who thinks he sees a ghost (which turns out to be donkey) on Bonnewells Lane in nearby Bransby and hopes the Black Dog will protect him: ‘It sure unnerved ’im, that it did, / To be theer by ’issen, / Until ’e thote about the Dog, / He warn’t so freetened then.’ Susanna O’Neill includes a chapter on ‘Black Dogs and Strange Encounters’ in Folklore of Lincolnshire (2013), as does Adrian Gray in Lincolnshire Tales of Mystery and Murder (2004), both of which cite some more recent alleged sightings, some of which are more sinister than those collected by Rudkin. They are certainly still said to happen: in 2023 a friend of this author, not prone to superstition, was certain he had had an encounter with a hugely oversized, apparently peaceful, slathering black dog in woods a few miles from Wragby, when he was collecting firewood; he is sure there is a logical explanation, but not what it is.

In October 2024, as part of this project, Adverse Camber Productions and the storyteller Pyn Stockman spent a week at St Mary’s Catholic Primary School, Brigg, where year 4 chose to develop a play based on Tattercoats, blending it with Black Dog legends.

The earliest mention of ethereal, giant black dogs in England is an entry from 1127 in the inherently matter-of-fact Peterborough Chronicle, and reports the sighting of many huge black hounds belonging to a ‘wild hunt’ in what were then extensive woodlands between Peterborough and Stamford, around the southern border of Lincolnshire.

Words and images by RORY WATERMAN

Leave a comment