An old woman sits in the shadow of the Chapel, insisting that her neighbour Betty was a ‘real witch’. Is this the 1830s, when Betty thrived? No. It is the 1930s… A young girl running into a kitchen with an armful of ‘may’ blossom so terrifies her grandmother that the old woman would hurl her back across the threshold, if she were not so lame. Is this in the 1860s? No. It is 1961. We are in the Lincolnshire village where Mrs ‘Peter’ Rudkin, the pioneering woman archaeologist, still lives in her tall house of treasures down Long Lane, and, amongst so many other activities, still eagerly collects ‘folklore’.

I was the child with the unlucky hawthorn petals in her hair. I knew Mrs Rudkin, who with typical generosity, spent an evening telling me her own vision of her village’s history – then watched a schoolgirl hurry down Long Lane clutching a rare copy of Mrs Rudkin’s own classic book. Now I have done my best to bring the world of ‘Lincolnshire Folklore’ to life in a brand-new book, the work of a lifetime, called Village.

I am a poet, and a frequent broadcaster – about poetry – on BBC Radio 4. But Village is written in prose, and is as true as I can make it. Whenever possible, it has the voices of the villagers themselves. It is focused on six village homes, from the tiniest cottage, down Northfield Lane, to the Manor, perched high on the limestone of the Cliff.

‘‘She answered me right cheerfully’, sang old Alfred Bateman, farm foreman, to a song collector, who preserved from our village, in 1937, the fictional tale of an alarmingly young girl, ‘Seventeen Come Sunday’, which parallels the real single mothers – Victorian ‘Singlewomen’ – whose stories I tell.

For Village celebrates the cheerful survival of the people who lived in its six chosen houses – especially the women. I did not know until I had almost finished the book that my own hawthorn-hating grandmother was reputed to have second sight, as a dreamer of prophetic dreams. This startled me, although I knew the powers she brought to story-telling…

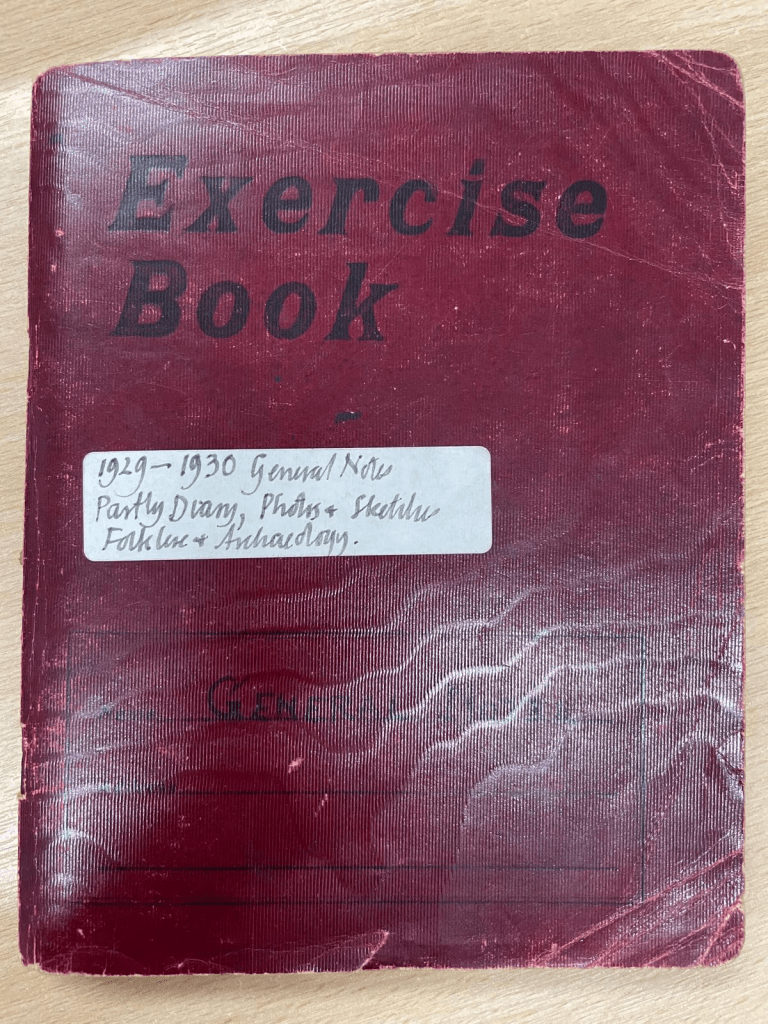

From the power of the Internet, from a tangled fragment in Mrs Rudkin’s notebooks, I discovered that Mary Ann, who lived for half a century in the village’s tiniest cottage, was believed, as late as the 1890s, to have murdered three people with the ‘spells’ she could cast from her home beneath the walnut tree.

And I explored a startling fact, which Mrs Rudkin was told in a January street… In our Victorian village, Mary Ann, unmarried, shared her home with a ‘Lodger’, a phenomenally skilled ‘Horseman’ who worked with great plough-horses, as his son and grandson would continue to do. His name was Isaac. His father had been brought to England by a Duke, possibly from the Carolina plantation which gave him his middle name. Isaac’s father was black.

Mrs Rudkin’s notebooks also reveal that, sadly, by the 1930s, Isaac was remembered by children only for – allegedly – gaining power over horses by cruel practices with toads. In fact, such ‘horse magic’ was widely reported in Eastern England amongst white waggoners. I knew one ageing waggoner who claimed to Mrs Rudkin that he himself had tried it… Less sensationally, the village coal merchant (whose blacksmith father had been killed by the power of a carthorse’s hind feet) reported a different reason for Isaac’s family’s horse-handling powers. They owned a ‘cud’, a piece of loose flesh, often found in the mouth of a foal. As I report in Village, the ‘cud’ is still kept, now to bring luck and health to the foal, and can be found firmly nailed above Gloucestershire stable doors!

‘I have seen the Black Dog’, Mrs Rudkin declared at the beginning of her finest article. This villager can only claim, humbly, that if she describes vivid living links to the traditions Mrs Rudkin described, it may be because she has twice found herself on the ground, and watched a horse’s hooves fly over, within an inch of her riding crash-helmet. Unlike William, Mary Ann’s shepherd father, who was ‘Killed by a Cart Wheel Passing over his Head’, I survived.

My grandfather (like William?) drove a shepherding cart. I have rattled along in it beside him. My father, like Isaac, ploughed with massive shires (and escaped death, under an overturned cart, thanks to the sheltering curve of a shaft). Like them, I have brushed furiously at the muddy silk of ‘feathered’ horse-heels. Village may be the last book whose author can bring the adrenaline rush of three generations of ‘Horse Keepers’ to Mrs Rudkin’s careful notes on the folklore she identifies, with characteristic optimism, as giving ‘Mastery over horses’…

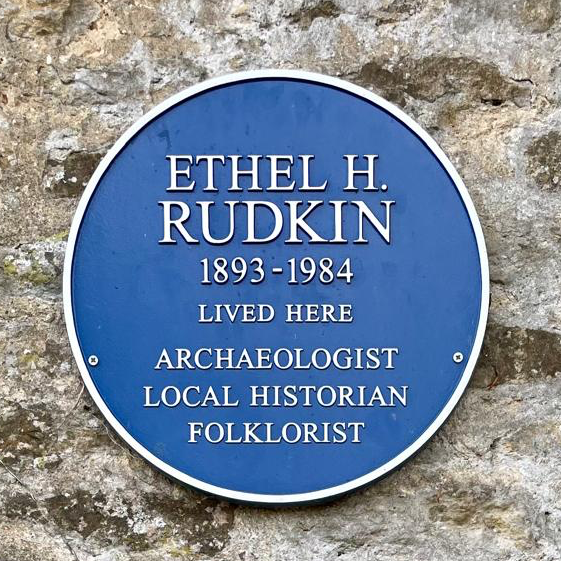

‘Who knew Mrs Rudkin?’ I asked a packed Lincolnshire audience recently. Nobody! I think she is in danger of slipping from view. Lists do not convey the brightness of her attention, or the authority of her voice. For half a century, she stayed in her village. She preserved its stories, and she gave them back. Village tells you how she opened the great door of Rose Cottage to any child bringing her a fragment of pottery; how she gave a history talk to the women of her village, amongst the best gilt tea cups in a farm cottage, just yards from where Jenny Andrew had assured her that Betty Wells was a ‘real witch’.

One shock of Village is that the cheerful, if superstitious wives of ‘labourers’ were likely to survive much longer than the rich young couples of Victorian farming’s ‘Golden Age’, who, like modern Yuppies, crashed and burned. Mrs Rudkin, of course, preserved glimpses of them. ‘Harriett’, flicking her whip over the pony-trap as her high-stepping pony sped away from Rose Cottage; the finely-dressed farmer – who built the Manor for his doomed young son and daughter-in-law – seen moving quietly amongst his cattle… as a ghost. I have gathered some more striking ‘seeings’ for Village. The ghost who sits down on your bed, may, by the way, be my own red-haired great-grandmother…

And my final recommendation of Village to enthusiastic followers of Lincolnshire folklore? It has a new story to add to the galaxy of tales about ‘Boggarts’… Ours is a Boggle! But it is not as friendly as Mrs Rudkin’s beloved Black Dogs. Do not venture along Kirton in Lindsey’s sinister Low Road, the site of at least one Victorian murder, with its deep hollows and dips, on a night of fog. You will never survive to read Village….

Village is available as a paperback or as a Kindle edition, but can only be bought online. Here is a link to the paperback. By following the link you will also find the Kindle edition, which is fully searchable, has live links in its Notes Section to songs and articles online… and costs a mere 99 pence! Frugal villagers would approve…

Words by ALISON BRACKENBURY

The project is immensely grateful to Alison Brackenbury for her contribution to the Lincolnshire Folk Tales Reimagined anthology (2025), as well as her contribution to the folk tale map post on Gibbery Gap.

You can buy Alison’s Village: Survival in Six Houses 1841-1971 (2025) by following this link. Alison also runs a blog that contains additional stories related to the book, and news about her latest projects: https://alisonbrackenbury.wordpress.com/

Leave a comment