We love receiving original contributions of creative writing. Below, you’ll find a new addition to the Jack tale genre, sent to us by Peter Irons, who came along to our recent Folk Tale Day at Mrs Smith’s Cottage Museum, Navenby in February. This story is set in and on the edge of the Lincolnshire Wolds, and in the past.

Jack mantled down the hill towards the town. As he neared it, the sounds and smells from the street vendors rose to meet him. All he needed here was an opportunity, a chance. Up in the village, where the wind blew cold, there were few opportunities for him to break out of the poverty which surrounded him.

At the bottom of the hill, just a couple of fields from the town, Jack sat down on a stone next to where the Waring ran across the track. In the water meadow next to the ford, the morning sun made the cattle glisten, and a steam halo rose up from the back of each.

Jack was dreamily watching the trout as they rose lazily to catch the odd fly that had settled on the emerald-green crowfoot hanging in the swift water. Unnoticed, a hagworm slithered up to him, shapeshifted into a pretty young lady, and sat next to him on the stone. Then she started whispering into his ear. He turned to her, startled and tongue-tied.

This picture of beauty told him about a mare that would be sold that day at the fair – a scruffy beast who would be in foal.

Whispering to him, she informed Jack that the White Stallion of Hoe Hill was the father of the foal and the mare had kept escaping onto the Heath behind the village. The owners wanted rid of the bag of bones, not realising that she was in foal. He could get it for a Crown, five shillings, which she would give him. That night, he could take the mare home to his mother. The beautiful lass said that the foal would become a great stallion.

Jack was spellbound – then, suddenly, she was gone! Putting his hand in his pocket, he found a crown! A whole five shillings! He had no idea how, but he felt he knew what he had to do.

Jack proceeded into Horncastle, through the North street, and to the Bullring, where on other days he had watched the older men cheering and drinking as British bulldogs were set free to attack a bull. There, on some fair days, a bull would be held by a rusty, heavy chain, through the ring in its nose, to an iron ring in a huge immovable stone. The more blood, the louder the cheers! Not today though.

Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of horses were lined up around the Bullring, and along the High Street towards the Market Place and the town bridge, which crossed the beautiful chalk stream full of fat trout, water cress and even more of that glistening, glowing, gorgeous water crowfoot.

Something drew his attention to a sad-looking mare, a strangely plump bag of bones, that was lined up with others by the riverside. He could not stop looking at it! Had the shapeshifting hagworm whispered to him about which horse to buy? Was it still with him, as a dog or human guiding him towards the nag? He could not stop himself.

Stuttering, he took the crown from his pocket and offered it to the bedraggled farmer standing with his string of pathetic-looking mares.

“I want that one! Can I ’av it?”

The farmer looked at the crown, then back at the youth, then again at the mare. “It’s yours mate!), he said. “Take ’er with you.”

Young Jack took the bit of rope tethering the mare and, smiling, he made his way back up to the Bullring, up North Street to the Lane, then back to his village three miles up the hill. On the way, everyone he saw pointed and laughed, and some called him names, but he kept on walking, his head held high. He had bought his first horse ever! He felt great. No one could burst his bubble that day.

Along the lane, the boy sat down on a wide grassy verge. Most of the wildflowers had gone to seed, and crickets and grasshoppers bounced around them. The blackberries were ripening in the hedges, ready to eat. Life was good. The mare was almost serene, and munched away at rich green grass and yellowing wild grains. Jack thought he saw a smile on her face.

After half an hour they set off towards the ford. The mare seemed to walk more powerfully now she had eaten. It was still morning, and the sun was still getting higher in a blue sky. Happy, Jack sat next to a beck dipped his toes into the water; fat trout nibbled around his toes, and sticklebacks darted around, trying to avoid the jaws of those voracious tigers of the river. Dragonflies and damsel flies patrolled both banks.

Dipping his right hand gently into the water, he stroked the belly of a resting trout, then lifted it out of the water and dropped its struggling mass into the long pocket of his jacket. Then another, and there were two in his pocket for tea

Even happier, Jack triumphantly led his horse up the track towards the village. I was three steep miles away, but there were lots of blackberries and plums to eat, and sweet grass aplenty for the mare. It was not a fast journey, but there was no hurry. Jack did not like hurrying.

Eventually, the two neared the village. Looking back, Jack could still see the town, and felt he could still hear it and perhaps even smell it. He’d seen meats being cooked around town on wood fires, and sold on the streets to the thousands who had come. Looking back up to the village there were gorse and nut trees, but what stood out most were the many huge trees which had become rarer on the sides of the hills closer to the town. Much of the land was being put under the plough, more and more each year. In some sloping fields he was used to seeing oxen pulling ploughshares through what had once been virgin meadows of grassland that, at haymaking, had been full of flowers, bees, butterflies, crickets.

The village was quite large, and had several hundred people living in it. As it was a long trek to town, and returning was even harder, the villagers tended to trade with each other. Craftspeople of all sorts lived here, in small houses built with from the materials available on the heath and in the valleys leading down to the Bain and Waring.

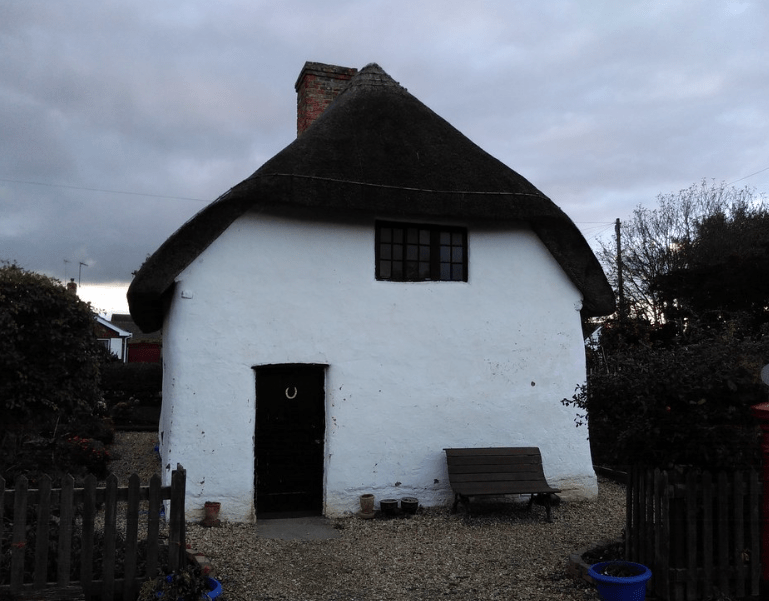

Jack and his mother lived in a cottage of a mud and stud – common up in the Wolds. When he was younger, he had been told how his great-great-grandparents had built it themselves, with the help of their friends, next to a lane at the top of the village that backed onto the Bluestone heath. There, they had been able to collect the sticks they needed, and mud from

some of the soggy, boggy ings where the becks started, on the sides of the steep slopes. Their

cottage had a ground floor with a fireplace, the only stone in the house, which took smoke up through the heather thatch. Jack slept in the loft, above the ceiling: at night, he climbed the ladder through a hole in the ceiling, next to the chimney stack. The warmest place in winter.

There would be no shortage of food for his pregnant mare. He could lead her straight out of their yard and graze her on the heath, just like the other villagers. There was no landlord or owner involved: this had been the right of the villagers since before living memory.

Finally he arrived at the cottage. His mum came out of the house in tears. Jack had been away for ages, and she had been robbed! All her savings had been taken – savings which were intended to get them through the winter. Five shillings – a crown!

Had the day just been a dream? But the bedraggled, bony mare behind him told him that it must have been true, and the two fat trout in his pocket meant that at least he had had fun down by the ford. He withdrew them from his pocket and handed them to his mother.

“What on earth is that bag of bones,” she blurted, nodding towards the mare.

“She was for sale, mum. Nobody wanted her, and the farmer said if I took her away I could have her!”

He definitely did not want to tell her about the crown he had found in his pocket.

“I will look after her ma! Anyway, I think she is in foal.”

Day after day, Jack took her onto the heath and to places of sweet grass which he knew about, but he never let her off the rope. His mare fattened, and her legs straightened. Right through winter and Spring, Jack looked after her, and she grew stronger and stronger, fatter and fatter. He even impressed all the farmers in the village, who started commenting on his skills and hard work.

Outside, he had but a crude shelter for her, to get her through the winter, but she survived, and even thrived. On May Day, he went to see her after he awoke, like usual, and there, standing next to her, was the most perfect young white stallion he had ever seen.

He called out to his mother, and she came into the yard, eyes wide and mouth open, shaking with excitement.

She hugged Jack, now becoming a strapping young man, and both realised they were going to be wealthy. In a couple of years, they knew people would be willing to paying up to £20 to have their best mares put to him, perhaps up to forty times year!

It has been said that Jack and his mum cunningly kept a low profile after this. Jack turned into a very efficient investor and regularly took the stage down to Boston where there were many banks financing adventurers as they set out to travel around the world. He might even have been involved in the financing of people traveling to Australia, but we can’t know for sure: the banks behaved as all banks do, and were sworn to secrecy. He might even have been a reason why such fine horses came to be bred in the Wolds, and why the Horse Fair became perhaps the most famous in the world, the place to go to buyers from all across Europe. Even Warhorse might have been inspired by such farm horses. And it has been said that, a few years later, Jack and his mother sold the stallion, jumped on a stagecoach to Boston, and were never seen again.

Author comment:

My stories reimagine the past. The oral history of this area seems largely to have been lost, so I create new tales – probably just as valid as the old ones that were told in the mud and stud houses of the Wolds.

Biographical note:

Peter Irons is 77 years old, and lives in Horncastle. He is a zoologist/biologist/ecologist, and his present project focuses on reversing ecological decline in a Lincolnshire catchment. He was an edutainer/teacher for many years.

Leave a comment