Borrowing wording from Theo Brown’s 1958 essay on the subject, the ubiquitous ghost in question – which I find my work now haunted by – is known regionally as Black Shuck, Gytrash, Barguest, Moddey Dhoo, Padfoot and Skriker: broadly, the Black Dog. Typically identified as a black canine that might originally appear as a normal dog, but in some way shows itself to be something other: ballooning up in size, staring with eyes as large as saucers or red and fiery, appearing out of nowhere or disappearing through solid objects. The Dog often portends death, illness or misfortune, but can also act as a protector against harm, accompanying solo travellers at night or leading to the discovery of hidden treasure. The Black Dog is a varied and complex legend, with most British counties having their own name and character for it to inhabit.

Having followed the tracks of the Dog through Britain for over a year, seeking to bring to life – or, perhaps, necromance – the legend through drawing and print, I now feel a close connection with the apparition. The Dog stalks through the corners of my vision in dark spaces, where I imagine the path he might take through the space, and lingers in the margins of my notes where I absent-mindedly sketch him – my hand remembers the shape.

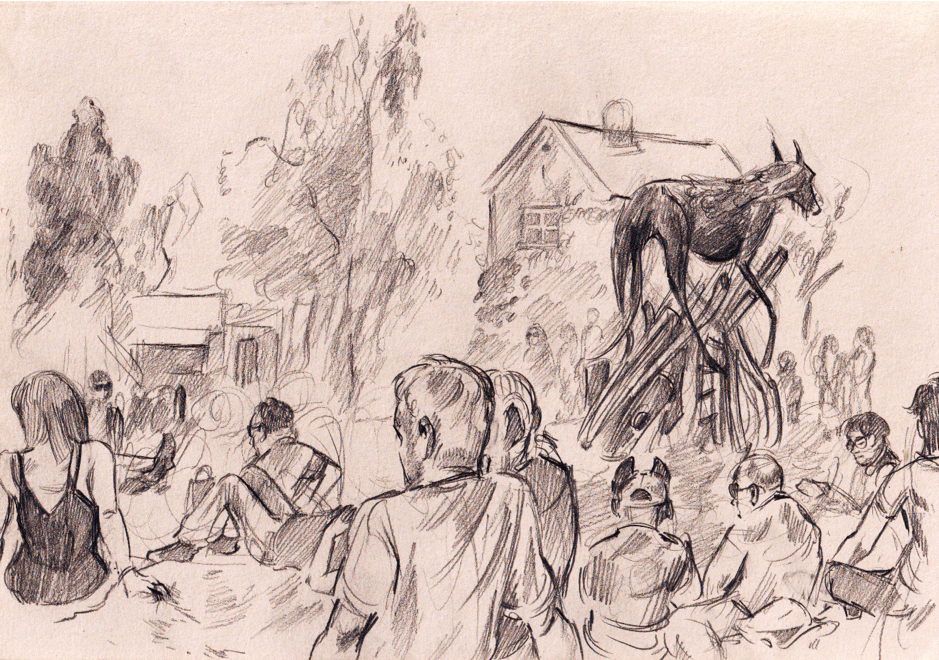

In October of 2023, I enrolled as a PhD candidate at the University of Leeds to begin work on my practice research project studying the animal folklore of Britain, and the eeriness that pervades it. In my proposal, I stated my intention to create a modern bestiary, populated with observational drawings from natural history collections, on-location at the source of legends, and imaginative works illustrating the lore I would study, melding my sketches with the fantastical stories.

My starting point for this plan was the Black Dog, an apparition so common throughout Britian that I already knew of several localised legends. As I began my literature review of the Dog, all sources seemed to point towards folklorists Ethel Rudkin (1893-1985) and Theo Brown (1914-1993), and the archive that holds all of Brown’s, and some of Rudkin’s, work on the subject.

My first entry into the archive was overwhelming. Where I had expected expanded notes from Rudkin and Brown’s articles on the Dog – in Lincolnshire and in Britain, respectively – for the Folklore journal, I was met with a huge expanse of information. Folders and manila envelopes strain against the volume of Brown’s notes: scrawled writing on scraps of paper, amassed newspaper clippings, letters detailing personal encounters with the ghost, annotated book scans and unpublished manuscripts. Rudkin’s notes take the form of a rusted ring-binder full to the brim with collected accounts, typed references and hand-drawn maps of her local legends, drafts and redrafts visible in light pencil sitting beneath the ink. It quickly became apparent that the study of the Black Dogs (and their theorists) alone would demand the full duration of my research. In the same way the Black Dog is often seen to phase in and out of place, shifting shape and form, the project stirred, shifted, and formed a new silhouette.

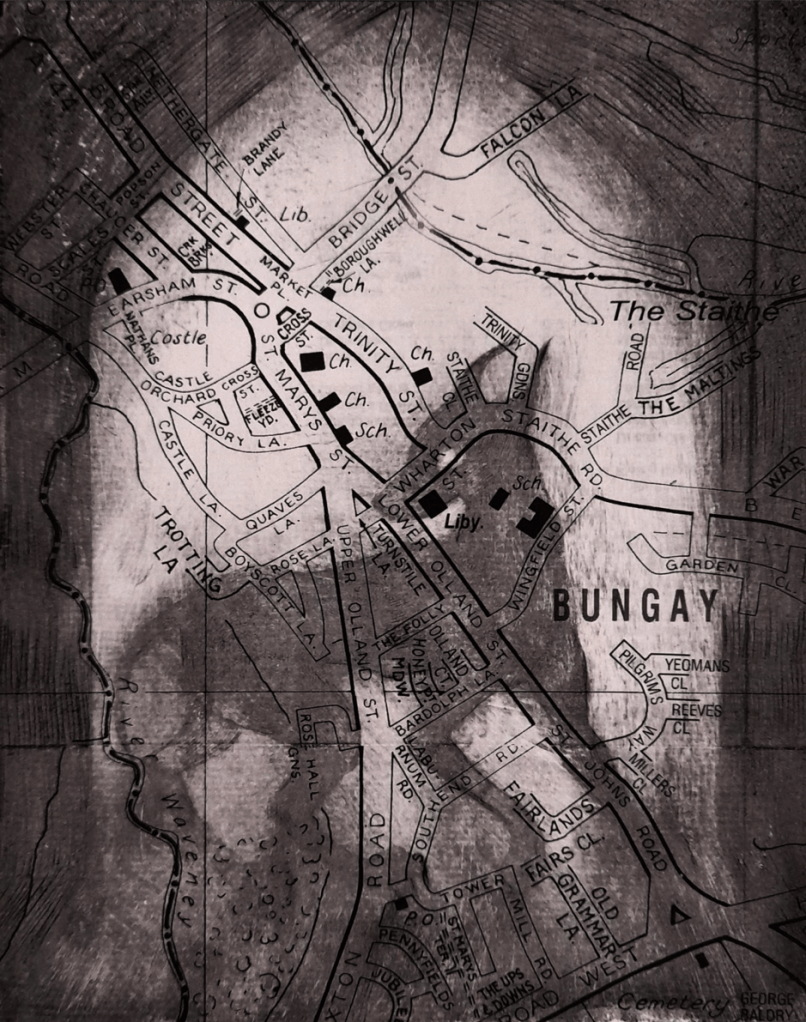

Now over a year into my studies, where the key focus has become darker and wiry-haired, my intention to draw from observation has persevered. I have drawn from archives of natural history, where dusty canine skeletons and taxidermy coyotes were carried out from storage by careful hands; from collections such as Lausanne’s Palais de Rumine, where a culled local wolf now resides indefinitely; and from the proceedings of the Black Shuck Festival, where locals and travellers annually descend upon the town of Bungay in Norfolk to relive the legend. My imaginative works make use of these drawings, synthesising observations of the physical with accounts of the spectral to produce drypoint and acid etchings depicting the Black Dogs in their many forms.

Printmaking is often described as an alchemical process: the application of metals, powders, wax and acids, incorporating heat, fire and water, to conjure an image onto paper. It is often aligned with ‘otherness’, set against an art world which might favour painting as the purest form of expression, and holds a unique eeriness in its “essential multiplicity”: that someone else, somewhere else, might be viewing the print at the exact same time. In this way I find printmaking, specifically etching, to be a sympathetic medium to capture the Black Dog: it exists in multiples, slightly different each time; it conveys a sense of the eerie and other, and it holds a sense of the alchemical and mystical in the process of its making.

My continued interest in Black Dogs is compelled by the vibrancy of collected accounts. In Roborough, Devon, a Black Dog appeared to a lone traveller, allowing his hand to pass through it, yawning and releasing a great plume of sulphurous breath, before disappearing in a great flash of light. One account collected in Brown’s notes tells of a Black Dog in Coate that appears at the site of the “Thyme Tree” – a space where no such tree grows, but where one can catch two whiffs (and no more) of thyme in passing – guarding the spot with watchful saucer-eyes. An encounter in Lincolnshire documented by Rudkin sees the Dog brush up against a local farmer: “it was like a pig’s skin rubbin’ agen me, bristly, an’ not like a dog’s coat at all!” The Dog commands our senses: blinding us with light, a dark shape lurking in the hedgerow, creating miasmic clouds of breath, touching our skin with boar-bristle fur. The purpose of my practice exploration, now and going forward, is to add a further dimension to the legend of the Black Dog. I hope to produce a visual illumination of the moment of encounter, capturing the unique and enchanting qualities of each account, allowing the Black Dog the space to continue to haunt our imaginations.

Words and images by KATIE MARLAND

The Lincolnshire Folk Tales Project is deeply grateful to Katie Marland for writing this blog and sharing her art.

Katie Marland is an artist and practice-led PhD researcher at the University of Leeds. She is conducting an investigation of the Black Dog folklore of Britain, the eerie, and enchantment, explored through drawing and printmaking. She is a self-identified vermin in residence – that is, an artist that was not requested nor can be gotten rid of – in various museums and archives around the UK. Her work can be found on her website or on Instagram.

Additional reading:

Brown, T. 1958. The Black Dog. Folklore. 69(3), pp.175–192.

Coutts, N. 2018. Animal Print Suicide. In: Pezler-Montada, R. ed. Perspectives on Contemporary Printmaking: Critical Writing Since 1986. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp.219-223.

Harding, R. 2018. Print as other: the future is queer. In: Pezler-Montada, R. ed. Perspectives on Contemporary Printmaking: Critical Writing Since 1986. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp.104-113.

Hewett, S. 1990. Nummits and Crummits: Devonshire Customs, Characteristics and Folk-lore. London: Thomas Burleigh.

Rudkin, E.H. 1938. The black dog. Folklore. 49(2), pp.111–131.

Leave a comment