Tim Davies

In two of her books of dialect fiction, the folklorist Mabel Peacock (b. Bottesford, 1856; d. Kirton Lindsey, 1920) includes several reworkings of traditional folktales. Her retellings are worth considering because she is a skilled storyteller in her own right, and allows herself to be unfaithful to her sources; it’s also interesting that none of the tales she chooses to retell is native to Lincolnshire. Here we’ll look briefly at how she alters traditional tales, localising them and changing their emphasis.

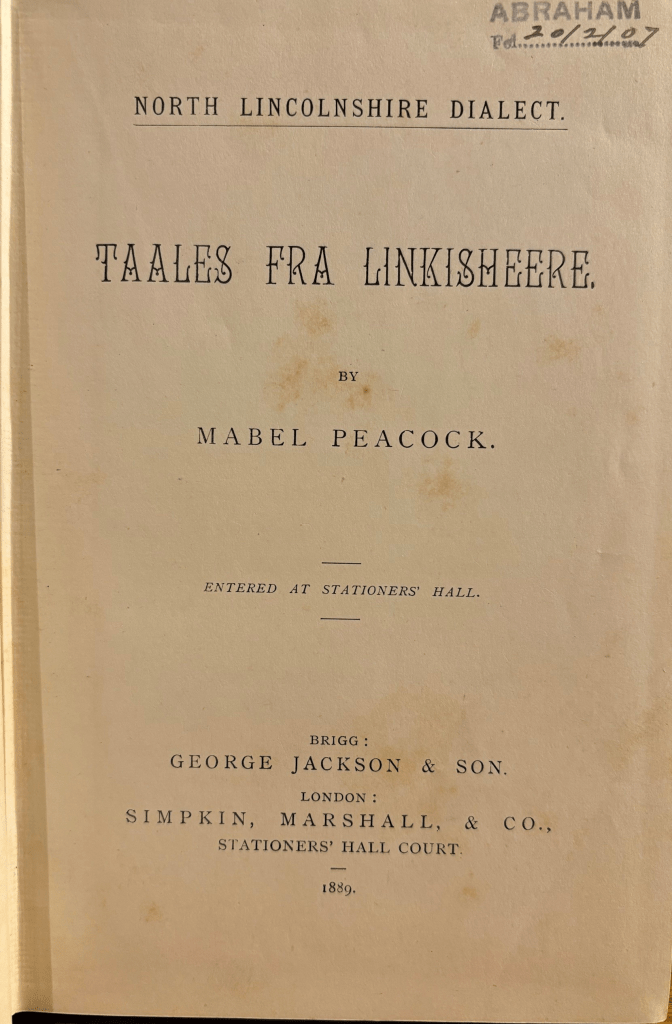

Peacock’s Tales & Rhymes in the North Lindsey Folk-speech (Brigg, 1886) contains three retellings of known folktales; herTaales Fra’ Linkisheere (Brigg, 1889) has one retelling and eight of Aesop’s more famous Fables. Both books are entirely in local dialect, and, taken together, this traditional material is roughly half the two books’ prose narrative content.

It’s perhaps not surprising that Peacock should be interested in trying local versions of traditional stories: she knew of the activities of mainstream tale-hunters like Andrew Lang and Joseph Jacobs – both of whom published Standard English collections which are still known and used today[1]; she was also, along with her father and siblings, an authority on local speech, and her family were almost certainly native dialect speakers. For someone of her lively and wide-ranging intellect, combining an intimate knowledge of ‘folk-speech’ with an enjoyment of old stories was doubtless a tempting exercise.

Boggards, graves, fools and bull-heäds

Notably, Peacock discards many of the traditional fairytale trappings: all of her stories are firmly rooted in the everyday realities of life in rural Victorian Lincolnshire, even when they feature the supernatural. Thus, the boggard in ‘Th’ Man An’ Th’ Boggard’ comes across as a work-shy chancer, familiar anywhere, rather than a credibly malevolent, otherworldly threat; ‘Th’ Lass ’At Seed Her Awn Graave Dug’ is a version of the ‘Robber Bridegroom’ tale-type, but here takes place entirely in a local farming community.[2]

Two longer retellings develop this approach to great effect. ‘Th’ Lad ’At Wantid To Larn To Shuther an’ Shak’ transports the Grimm brothers’ ‘The Boy Who Went Forth to Learn Fear’ from the world of capricious kings and haunted castles to a local mill.[3] The supernatural jeopardy our hero faces has a distinctly ‘Linkisheere’ flavour, and the miller’s daughter is no helpless princess. Her practical common sense complements the lad’s unaffected bravery, and assures her an equal status in their later relationship:

‘[I]v’ry neet as cums, duz th’ lad begin to talk to hissen i’ his sleep…”Aw, if I nobbud could shiver an’ shak!”

“Well,” thinks his wife to hersen, “it shan’t be my fault if ye doan’t.” Soa she fills a pail o’ watter full o’ flap-taailed bull-heäds [tadpoles], an’ all mander o’ wick things; an’ when he begins ageän, she souses it all on top o’ him.

“It’s a pity fer th’ beddin’,” says she, “bud it’s teäched ye what ye wanted to larn, hesn’t it?”

“Ay, it hes that,” says he, when his teeth’s dun chitterin’. “I doän’t mind boggards, but these here slippin’, slitherin’ bull-heäds, thaay’ve gi’en me shaks enif to last me a life-time.”

“Well, then, doan’t let’s hear ony moore on yer oud stitherum,” says she.

“Ye shan’t,” says he, “not if ye’re agooin’ to gie me sich anuther lessin’ as this, that I assewer you on.”

‘Th’ Lad ’At Went Oot To Look Fer Fools’ (better known as ‘The Three (or Six) Sillies’, and published as such by both Jacobs and Lang) concerns a young man who one day finds his fiancée and her parents paralysed by worry over a remote, imagined, threat to their unborn children.[4] He leaves, vowing only to marry her if he can find three people sillier. The standard version ends with his return, mission all-too-easily accomplished.

Peacock keeps the overall structure intact, but changes two significant elements. Instead of the imagined threat being a falling hammer, the family worry the children will fall down an unfenced well in the garden; she also expands the ending with an unexpectedly vicious twist:

‘[O]wd man put a raalin’ roond well; nobbud when childer begun to cum ower thick an’ fast he pulls it up ageän, an’ says to his wife, ’at he’s sewer, if Loord meäns to tek ’em, a bit o’ fencin’ wean’t stan’ i’ his road. Bud not long efter that theäse here burial-clubs cum’d up, ye knaw, an’ then bairns begun deein’ afoor iver thaay was big enif to creäp doon gardin’ to well. If Loord didn’t tek ’em, sum’ats else did…’

An unfenced well is more likely, perhaps, than a hammer falling from the roof-beams; they’d have been a familiar sight in contemporary farmyards and gardens. As for infanticide and insurance fraud, they are – we hope – less common, but certainly more down-to-earth than the more traditional ‘happy-ever-after’.

An’ that’s end on it…

This isn’t the only example of Peacock “strengthening” the ending of her source material, though it is the hardest-hitting. It’s a good example of her penchant for familiarising the fantastic and giving these imported tales a local identity. Combined with the conversational informality of the dialect narration, her fictional world is made to feel recognisable, and she gives herself room to point up the foibles – and strengths – of human nature, in an engagingly relatable way.

Tim Davies has been the Local Studies Librarian for North Lincolnshire Council since 2014. He has a particular interest in promoting northern Lincolnshire’s often-overlooked literary heritage, and has a very soft spot for the nineteenth-century folklorist and author Mabel Peacock. When not talking about Mabel Peacock to anyone who will listen, he enjoys walking, singing and drinking real ale in cosy pubs.

[1] Andrew Lang’s “Coloured” Fairy Books – for our purposes here, especially The Red Fairy Book (Andrew Lang, 1890); Jospeh Jacobs, English Fary Tales (David Nutt, 1890). See further n.4.

[2] See the Folktexts website, ed. D. L. Ashliman https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/type0955.html#fox [accessed 25 October 2024] for the mainstream text and two English variants which are suggestively similar to Peacock’s.

[3] Original at https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/type0326.html [accessed 14th November 2024]. Peacock’s version has slightly more affinity with the Grimms’ earlier ‘Good Bowling and Card Playing’, included on the same website.

[4] Jacobs’ version can be read here: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7439 [accessed 25 October 2024], and Lang’s here: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/540/pg540-images.html#chap17 [accessed 18 November 2024]. The tale was brought to the attention of all three authors in the pages of the subscription-only journal of the Folklore Society in the early 1880s. We should note, though, that Peacock published her account four years earlier than Jacobs and Lang. Thus our Lincolnshire variant may be the earliest to be made available to a general readership.

Leave a comment