Rory Waterman, who leads the Lincolnshire Folk Tales Project, discusses what planted the seed.

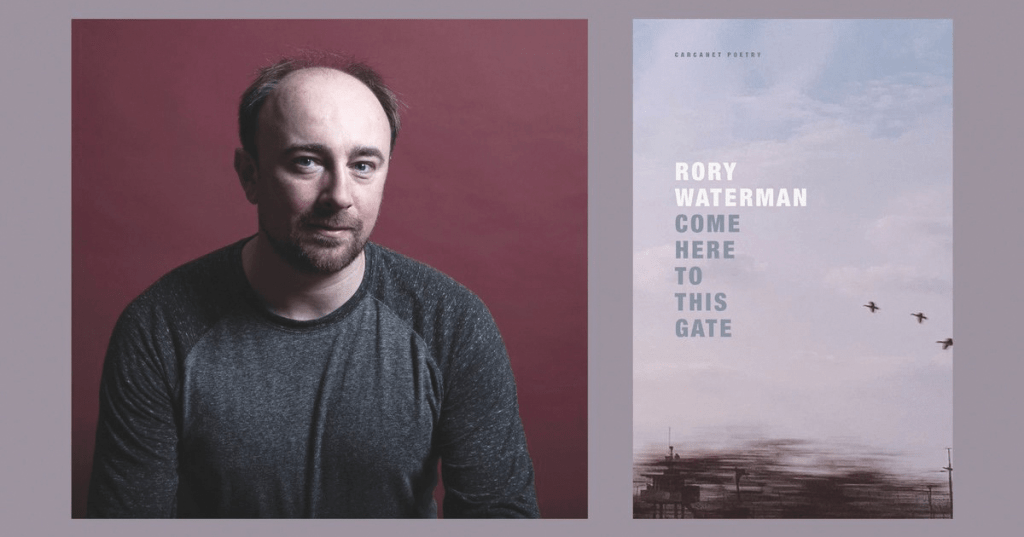

Six months ago, to the day, my fourth book of poems, Come Here to This Gate, was published by Carcanet Press. Among other things, it contains some, er, ‘modernised’ retellings of folk tales from Lincolnshire, incorporating several of my friends, plenty of mischief, and perhaps a few serious points too – some inherited from the stories, all inspired by what is in them.

Books take a while to come out, and these poems, all of which are ballads that present my take on traditional stories, were written in the winter of 2021-2. I don’t think I have ever had more fun with a pen in my hand than I did when I wrote those poems, but saying so requires me to compartmentalise experience. My dad died that winter, after a protracted illness and a series of other related tragedies. Writing these poems was my escape, my guilty pleasure between worrying, visiting, and trying to sort things out, and I laboured over them as much as I have over anything. And, of course, I also researched the heritage of my home county in a way I never had before, proud Yellerbelly though I am.

I was born in Belfast in 1981, but two years later my mum moved with me to her mother’s house, a lodge halfway between the small villages of Nocton and Dunston, about eight miles south-east of Lincoln. She had grown up in Dunston, and my grandmother had spent almost all of her adult life within a mile of our little gingerbread house, as my friend Sarah called it. My granddad had been invalided to Nocton Hall Hospital at the end of the Second World War, she had followed him up there from London, and they had settled for good. He worked for the big local farm, and died before I was born, probably as a result of the illness he sustained in Sicily in 1944, where he used to share his rations with street children. I wish I’d got to meet him.

It wasn’t until I’d moved away from home – first to university in Leicester at the age of twenty, then to Durham, then to upstate New York and Boston in the US, and then to Bristol – that slowly, incrementally, I grew to miss all I’d once had: the unspoilt woods miles from home that still felt like home, the down-to-earth friendliness of most people in this part of the world, the big skies in which you could read the weather forecast, the graceful features of a landscape outsiders write off as unremittingly featureless, the best cathedral on earth floating on the fields whenever I had gone into town. In 2012, I gratefully took the opportunity to live and work in Nottingham, dismissing two other opportunities elsewhere, because Nottingham was almost home. And I’ve felt gratefully reconnected to where I grew up, and where my mum and many of my closest friends still live, ever since, by an invisible umbilical cord.

Working on my versions of those folk tales, then, was an attempt to take myself back home, just when I most felt in need of its comforts. But writing the poems required a fair bit of research, a process I’ve been engaged with obsessively ever since, long after the poems were completed. I already owned Maureen James’ excellent Lincolnshire Folk Tales (History Press, 2012), and a few other books about local folklore, and had grown familiar with the stories they contained. It was in Maureen’s book that I first encountered ‘Yallery Brown’, the tale of a malevolent boggart-like creature who ultimately curses a lazy farm labourer. It had originally been collected in Redbourne, North Lincolnshire, in the 1880s, but I decided to move it to Chambers’ Farm Wood, near Bardney, and to make its protagonists my friends William and Sarah, who live in that area. Yallery is a convincing little blighter:

‘You’re a good lad, young Will. Don’t be frit:

I know all your dreams involve women and sloth.

I know you. Say one wish. I’ll grant it.’

I already knew the story of the Metheringham Lass, allegedly the ghost of a young woman who had died in a motorcycle crash after a dance at RAF Metheringham, because I grew up three miles away. I wondered what a modern encounter with her might be like, and what might bring it on:

She’s calm, but she’s been crying: doglegs

shimmer on her cheeks.

I offer the joint again. She shakes her head.

She’s cute, but reeks

of lavender and engine oil,

and what’s she doing here?

Someone had told me the cautionary tale of Nanny Rutt, set near Bourne, but I couldn’t find much information about it, so I took the opportunity to fill it with more of my friends and to put them in uncompromising positions. And the setting of the tale offered up a name that was impossible to resist:

Math Wood is a small plot of trees south of Bourne,

next to McDonald’s and Lidl.

It’s privately owned, full of shot-gun shells, pheasants –

but still, a bit of an idyll,

and Mike lived in Bourne, and Doreen in Northorpe,

a hamlet just south of the wood,

and Mike had got married, and Doreen had too,

and because they were up to no good

they’d meet now and then by the well in the middle,

kiss, fumble, roll on the loam

for a bit, then rush back for vigorous showers

before their spouses got home.

And of course I knew the famous tale of the Lincoln Imp. As he has become quite the commodity, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to slot him firmly into the secular world of commerce that we are all lumbered with:

Then he flew through the church – up the transept, the nave –

and swooped to the shop. It was frightening:

a thousand or more resin models of him

glared from shelves, so he left quick as lightning

and soared to a perch at the back of the church

to ponder a while on his own,

but an angel was trying to kip on the altar,

saw him, and turned him to stone.

I didn’t expect to publish these poems: most of the poetry I write stays locked away on my computer, and is never sent to a magazine, let alone included in my next book. I was just enjoying myself. But I thought they’d be fun to read aloud, and they went over very well at readings, so I changed my mind, and my wonderful editors at Carcanet Press agreed that I should. Initially, I put them together under the title ‘Lincolnshire Folk Tales Redux’, but the last word was expunged after my friend, the screenwriter William Ivory, said ‘Don’t do that! Own them!’ He was right: why shouldn’t I? They’re mine, these tales, as much as they are anyone else’s – and they can be yours, too, as much as they could ever be mine. Do what you like with these stories, if you’re a writer or storyteller. Folk tales are public property, and never can be definitive, which really appeals to me – but they do need to be told, one way or another, or they don’t multiply, they die.

The book came out. And then something surprised me: few people who heard my versions of these stories at readings, even back in Lincolnshire, seemed to know anything about the tales, or any of the others I had grown familiar with. Then it dawned on me that – though there are many excellent local folklorists of various kinds who care very much about our local folklore – most of the popular books of folk tales, or about them, tend almost entirely to overlook Lincolnshire in favour of England’s more fashionable places. I’d not really noticed that before. I started to feel sad about these things, not least because our folk tale heritage, I’d discovered, is every bit as rich as anyone else’s. And that is where the idea for this whole project, ‘Lincolnshire Folk Tales: Origins, Legacies, Connections, Futures’, began. This had not been my intention when I wrote ‘my’ tales, but getting stuck into something can, on occasion, take you in unexpected directions. It has continued to do so. And I invite you to get involved in this project and make it part of your journey, too, whoever you are.

Words by RORY WATERMAN

Rory Waterman, Come Here to This Gate, was published by Carcanet Press in April 2024.

Leave a comment