Have you found a boggartstone? To learn more, search #boggartstones on social media – and read on for a fascinating interview with the creator and distributor of stony boggarts around Lincs.

‘P’ the person behind Boggarstones project, is a heritage professional and artist who lives in south Lincolnshire. ‘P’ is interested in people, landscapes and history, and especially how these three overlap and intertwine. While the Boggartsones project is a folklore collecting endeavour, an equal aim is to help people discover, engage with, and discuss their local lore and the micro-mythology of their environs. By prompting this, traditions and superstitions might hopefully continue and maybe even develop. ‘P’ uses art as a randomised research tool, and so finds keeping their real-world identity separate from the project helpful.

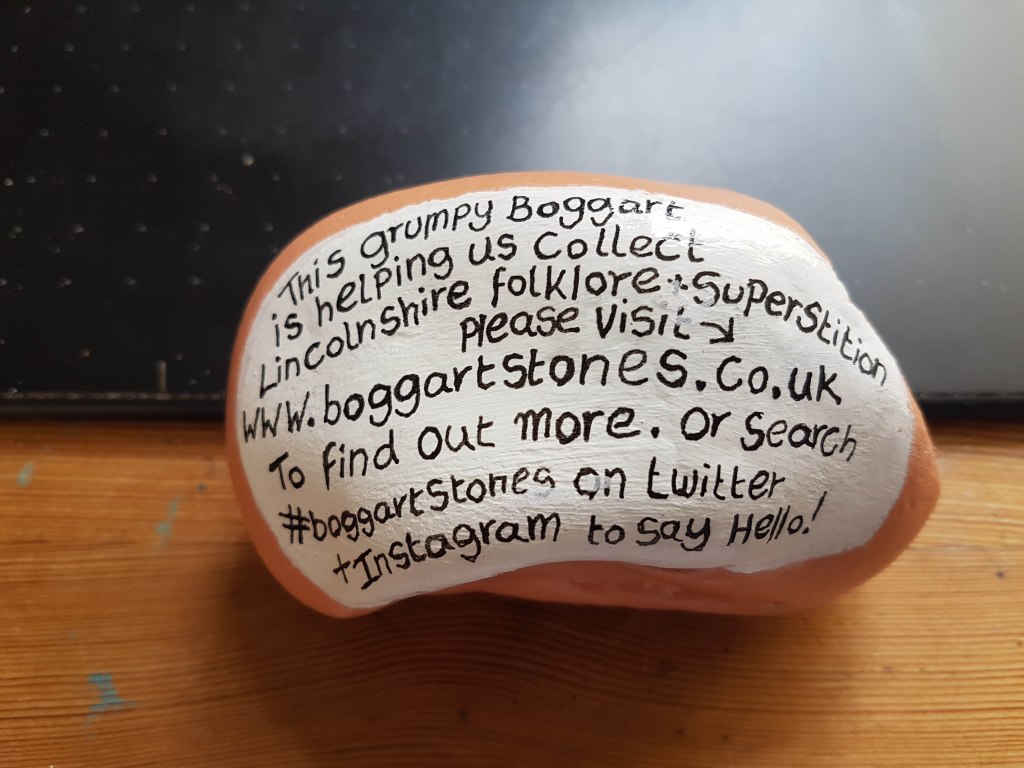

We discovered Boggartstones earlier this year, when Rory met one at Byard’s Leap. The interaction was one-way, until he turned it over and found a message that led to a conversation…

Where did the idea for Boggartstones come from?

I suppose this is rapidly becoming a modern cliche for projects, but it was during the first Covid lockdown. I had been reading through a copy of the Folklore Society’s County Folklore – Vol V, which covers Lincolnshire. I’ve had a lifelong fascination with folklore and myth and I’d previously made some short exploratory forays into writing about folklore. But now with this free time, and dipping in and out of this volume full of accounts and examples got my brain whirring. My day job involves a lot of work with maps, and I generally find when I’m getting interested in something, my first instinct is to locate it, pin down where it comes from. So, naturally I thought, why not add these entries to a map? But I was maybe a third of the way into this, when it struck me, this data has a cut off point. All this information, up to the publication date of 1908, then… nothing. And I thought, is there more still out there? Does any of this bear any relation to people today?

Why ‘boggartstones’?

I was thinking, how would I canvas people? I wanted to talk to people about their superstitions, their weird family good luck traditions. I wanted to see if people still had a connection to these stories and legends woven into the landscapes of Lincolnshire. But at that moment, we are all at home, in bubbles, living through zoom calls and facebook. Interaction was almost impossible. That’s when I noticed the stones appearing. I was already aware of this hobby some people had. Taking rocks, painting them and leaving them out for other people to find. But I’d never seen it as anything other than a cute pastime. But on my daily walks I started finding these brightly decorated stones. One day I picked one up and found a message written on the back, and it just clicked. Here was someone communicating with me. Here was a way I could maybe reach other people. I set up a website, and an email address, and started painting.

It’s a lovely idea. Is there any method to where you leave them?

In the countryside, walkers’ stiles make good places to leave them. Points where people are accessing or crossing something seemed appropriate. So gateways and bridges are favoured spots. In towns and villages, I may drop a few on the high streets, but I usually seek out parks and public spaces. I won’t leave anything on private property, and likewise I avoid cemeteries, places of worship or any areas dedicated to reflection, such as war memorials and the like. But, outside of those, anywhere else is fair game! I enjoy the chaotic nature of it. I could print posters, and have them put up in village notice boards. But only a certain kind of person will stop and read those. This way, I could be interacting with anyone.

I happened upon one at Byard’s Leap, next to the horseshoes that are meant to indicate where Byard, the horse, leapt while helping to vanquish a witch, in one of the county’s best-known folktales. It certainly made my visit more enjoyable.

Ha, Thanks. A lot of people have emailed or made contact on social media after finding a Boggart Stone, not to relay anything folk related, but instead just to say how happy it made them to find one. I think the act of discovery, of a piece of art in an unexpected or unusual place can be fun. But it also slightly jolts people into looking at possibly familiar surroundings with fresh eyes. A mum of one family told me how her son, who going into the summer holidays had begun to display the slightly grumpy, parent-weary attitude of the burgeoning teenage years, had found a Boggart Stone on a bike ride round their village. And had subsequently spent days with his mate looking for another, but instead relayed at meal times, discoveries of frogs, fossils, and a hollow tree which became a de-facto ‘den’ for the pair that summer. If anyone who finds a Boggart Stone has their curiosity piqued enough to maybe pick up a book on local history or spend a few minutes talking about a village ghost with a friend, then I’d consider it a win!

Do you have any favourite folktale-related locations in the county?

That’s a really good question, and a tricky one to answer. I think folk tales are so inherently woven into their landscapes, the ‘shape’ of the place moulds the story. Lincolnshire is such a vast and diverse county topographically, it varies so much as you cross it, maybe more so than any other county I can think of in England. The muddy Humber shores and the Carrs in the north sweep up to the cosy blanket bumpy landscape of the Wolds, and those are brimming with farming folklore and haunted airfields. The Lincoln Cliff, a sharp escarpment that runs north-south, interests me a lot. Dozens of small villages sit along the top and bottom of the slope, and there are so many stories of lantern-like lights, spectral dogs and figures meandering up and down the ancient lanes that connect the higher and lower hamlets. A spring might issue out of the hedgeline, into a field that contained a Roman Villa, or a WWII gun emplacement. There’s a sense along the Cliff of deep history, jumbled up with modern life. Some of the stories to be found around there are fascinating.

Have you confined your project solely to Lincolnshire? If so, what made you want to do so?

I was originally inspired by finding an original 1908 copy of the Folk-lore Society’s – County Folklore Vol 5, Examples of printed folklore concerning Lincolnshire. So that pretty much immediately settled the boundaries along the old county lines. Though as time moved along, I’ve realised that among the material collected by nineteenth-century antiquarians and researchers, there is a definite bias towards the north and north west of the County. So much so, it became clear the fens and the south of the region (where I live) had been much overlooked. I suspect several factors played a part, distance being one. Many of the researchers, by sheer chance, lived and worked north of a horizontal line that cuts through Lincoln east – west, and they would clearly call on the knowledge of communities local to them. But I also wonder if the less populated reclaimed fen farmland, with smaller disjointed communities, served by chapels not churches, sometimes distant to main roads and routes, might have presented a ‘tougher’ less idyllic environment to seek material in. A couple of references to the roughness of fenmen and the unwholesome marshy airs, might hint at snobbery playing a role. So I’ll admit, I am beginning to wonder if throwing the net further south, to include Whittlesey, Wisbeach, and Lynn, and taking in the fenland as an entire entity of its own might be worthwhile?

I think it would! That is, broadly, the approach Polly Howat took when she wrote Ghosts and Legends of Lincolnshire and the Fen Country in the 1990s. The border is in a sense arbitrary, isn’t it? Though I do think there’s a certain modern pride in Lincolnshire that runs across the county. Do you sense this?

Outside of council or tourism capaigns, I don’t feel there’s a pan-Lincolnshire sense of pride, in say, they way you see people claiming to be “Yorkshire & Proud”. Again I return to the diverse landscapes that Lincolnshire encompasses. I have farming friends, on whose Facebook accounts they describe themselves as fenlanders. You hear people telling others how proud they are of the Wolds, not Lincolnshire, but that small distinct area of it. The carrs and marshes, bear no similarity to ‘Tennyson’ country around Somersby. The lush landscapes around Stamford could be no more different to say, the Humberston Fitties. I think this disjointed patchwork turns people inward to ‘their’ area, their landscape. I do feel people from Lincolnshire are tied tighter to the land than other regions and loyal too it also, but specifically the bit that they recognise.

Might there be a Boggartstones book one day?

I suppose a book is the obvious expectation, but that feels… I don’t know, too linear? As I’ve gone along this road, I’ve become more and more involved in the world of ‘zine making, quick & dirty, zero budget self-publishing. Hand drawn, physically pasted down pics, home printed or run off on a library photocopier, the slightly punk attitude I think better suits a project that has functioned by injecting painted rocks with a question on the back into people’s lives unexpectedly. Possibly a hotch-potch compendium of zines. Each booklet a different story or subject? That way people could assemble their own personalised folklore library and read about the things important or local to them.

Do you have any further plans for the project that you’re willing to share?

Right now, I’m enjoying painting, travelling, and distributing the Boggarts. Talking ghosts, fairies and all sorts of oddness with people who find one and respond is always a highlight of any day. I’ve seen a lot of Lincolnshire, but there’s still more to explore. Some sort of exhibition seems likely in the future, but where and when are still to be arrived at. There are a couple of locations in the region that I feel would reward much more detailed examination. But for that I’d need much higher levels of engagement. I might look at other sorts of ‘interventionist art / research methods. Keep your eyes open, you may be seeing us on your streets in the future!

Interview conducted by RORY WATERMAN

Leave a comment