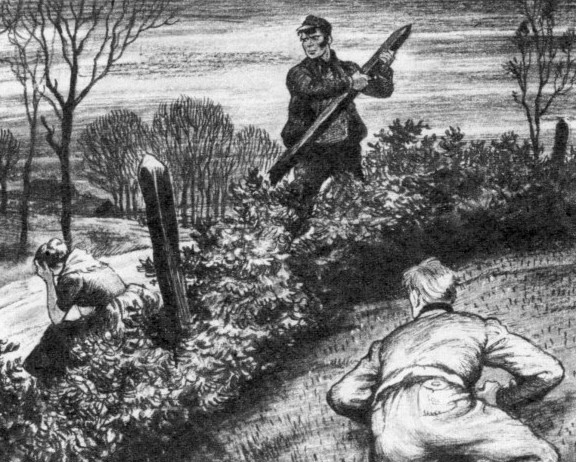

This is a horrifying true story that fed macabre imaginations and thus also became a legend. Tom Otter, a twenty-three-year-old native of Nottinghamshire and a navvy working near Lincoln, made local woman Mary Kirkham pregnant in 1805. He already had a wife and child back home, but the authorities who forced them to marry in a ‘knob-stick wedding’ in South Hykeham were unaware of that, and to disguise his identity Otter used his mother’s maiden name, Temporal. After the wedding, and apparently incensed at having had to pay a ‘bastardy bond’ for the upkeep of the child, Otter killed his new wife with a hedge-stake at Drinsey Nook near Saxilby. He had apparently lured her there, possibly with the promise they were heading off to start their life together.

Mary’s body was discovered the following day, and taken to Saxilby, possibly to the Sun Inn, which still exists. All the (plentiful) evidence used to convict the killer was circumstantial, and one day later he was arrested in Lincoln and taken to the gaol in Lincoln Castle to await the Lent Assizes.

Otter was tried on 12 March 1806, sentenced to death, and hanged at Lincoln Castle two days later. His body was subsequently coated in pitch and displayed in a gibbet close to the scene of the crime, where it remained until the whole thing fell down in a storm in 1850. He was the last person to be gibbetted in Lincolnshire. In 1811, newspapers around the country reported that blue tits had nested in the skull, inspiring this rhyme (and close variants of it):

There were ten tongues all in one head.

The tenth went out to fetch some bread

To feed the living within the dead.

This is in fact a variation of riddle associated with a common tale type, known as ‘out-riddling the judge’, in which a convict can be freed if (usually) he can provide a riddle that the judge cannot answer. More often than not, the riddle in question relates to a nest of birds, often made in a horse’s skull. The irony of the above rhyme is obvious, once this is known. Tales of this sort were once common in England, and to some extent throughout much of Europe and in parts of the USA.

Tall stories arose almost immediately. According to Thomas Miller (1807-74), whose account was published in the Lincoln Times in 1859, ‘the cries of a new born child were always heard in the room where the murdered woman was placed’ on the anniversary of the marriage and murder. Kirkham’s blood was said to have stained the steps of the Sun Inn when it had been brought there, and the blood was claimed to have been impossible to clean off for many years afterwards. The nearby Foss Dyke was said to have run red with blood when Otter’s body was taken across it, and his hand to have grasped when his body was being raised in the gibbet. The hedge-stake that had been used to commit the murder would allegedly return to be found at the murder scene every year, despite being fixed to a wall with iron, until it was burned by the Bishop of Lincoln in Lincoln Minster Yard. There’s no evidence for any of this. Miller’s article claimed to include a deathbed confession from a local labourer called John Dunkerly, who claimed to have witnessed the murder: he allegedly described the second blow to Kirkham’s head as like someone hitting a turnip. There is also no hard evidence that Dunkerly existed, though he now crops up as a real figure in most accounts of the murder and its aftermath. Miller was consciously fictionalising history, as his covering letter (preserved in Lincolnshire Archives) makes clear. Chris Hewis’s article outlining this was published in Lincolnshire Past and Present in 2013, and can be downloaded here.

One further legend that grew up, presumably through the natural exaggerative processes of gossip, was that one Jack (not Tom) Otter had been married nine times and had murdered all of his wives, and ‘one day he was angry with the woman he was courting, and whom he intended to take for his tenth wife’ so he ‘called her to go for a walk with him, and when they had got into a lonely place he stabbed her on the spot’, which led to him being gibbetted here when the crime was discovered. This version is from S. O. Addy, Household Tales (1895), and is included by Gutch and Peacock in Examples of Printed Folk-Lore Concerning Lincolnshire (1908); Addy relays it as fact.

‘You can’t make this stuff up – well, someone did, obviously’, as Bob Ebdon said when introducing his entry for Write a Lincolnshire Song in 2014, which you can listen to below. The folk musician Mossy Christian has adapted the folk song ‘The Apprentice Boy’ to the tale of Tom Otter, and incorporated the rhyme above into the song’s ending when he performed it at the Lincolnshire Folk Tales Project / Heritage Lincolnshire ‘Lincolnshire Lore’ event at The Lawns, Lincoln, on 31 August 2024, noting the uncanny nature of the similarities between that folk song and the macabre events surrounding Tom Otter.

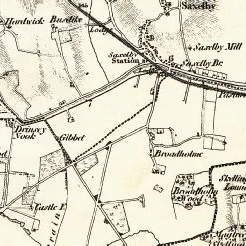

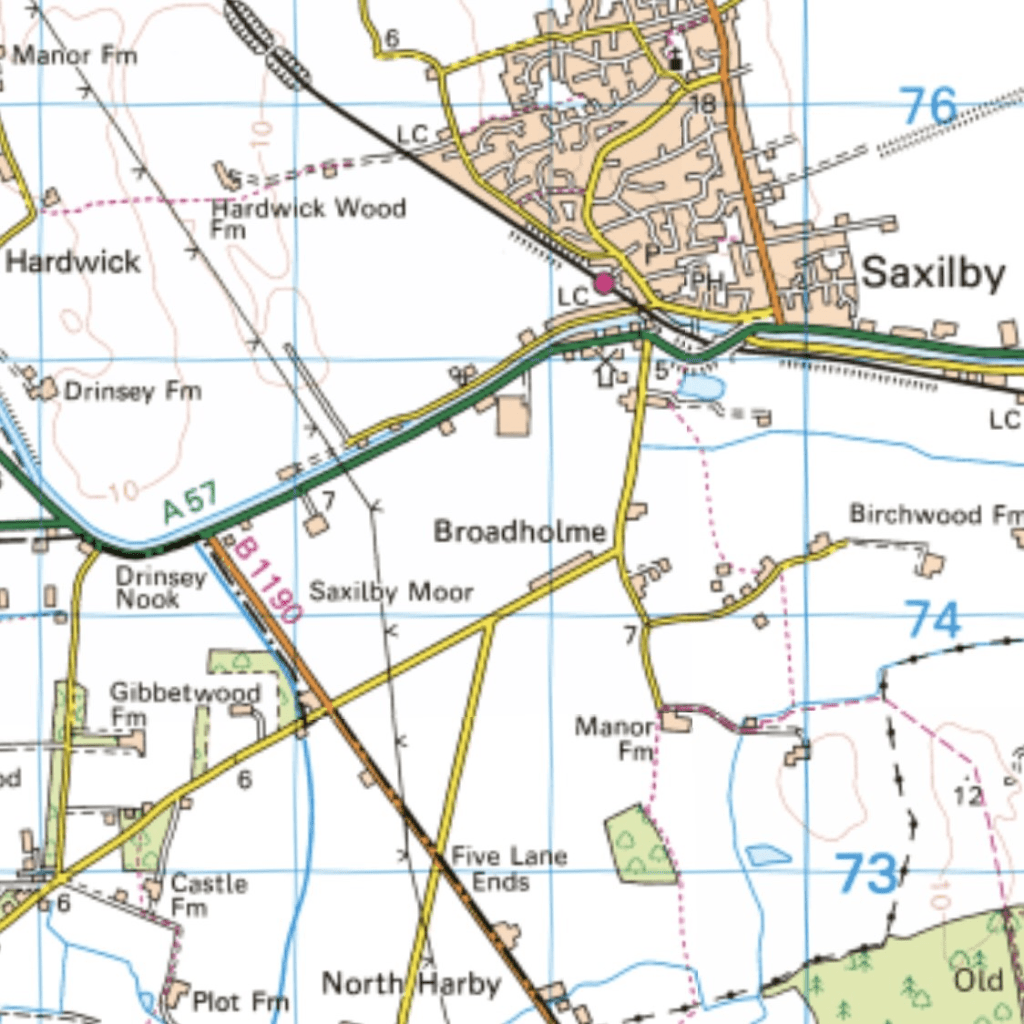

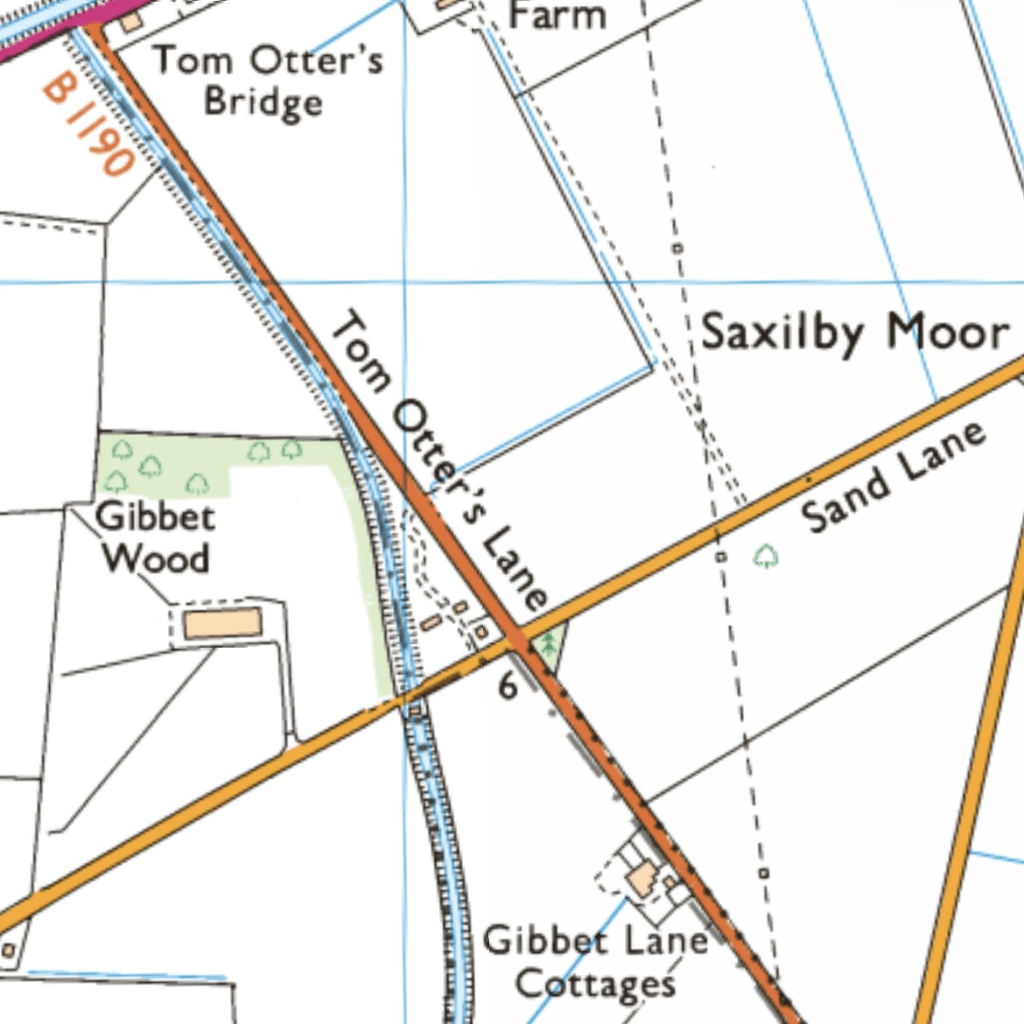

The country road where the murder occurred, and where the gibbet was mounted, is now called Tom Otter’s Lane. According to the 1828 Ordnance Survey map, the gibbet was located halfway between Sand Lane and Gainsborough Road (the A47). At the north, Tom Otter Lane ends at Tom Otter Bridge. An address on this lane is Gibbet Lane Cottages (also known as Gibbet Farm), evoking an earlier designation. Halfway between the bridge and the cottages, close to where the gibbet stood, is Gibbet Wood. Mary Kirkham was buried in St Botolph’s churchyard, Saxilby, though if her gravestone remains it appears to have weathered to the extent it can no longer be deciphered, and her name is virtually lost to history and human geography.

The gibbet head-collar and part of one of the gibbet legs are owned by Doddington Hall, a few miles south, and usually on display there. They are currently on loan to Lincoln Castle, and on display in the Magna Carta Vault, along with a nutcracker fashioned from part of the gibbet that is from the collection at the Museum of Lincolnshire Life.

The Saxilby History Group maintains a detailed webpage about the facts and folklore. The website Michelle Barber and Mystery contains a trail, information about the various sites associated with this crime and its punishment, and some intriguing suppositions. Susanna O’Neill discusses the fact and myth at length in Folklore in Lincolnshire (2013), as do Adrian Gray in Lincolnshire Tales of Mystery and Murder (Countryside, 2004) and Stephen Wade in The A-Z of Curious Lincolnshire (2011), who notes that ‘it has all the elements of a folk tale’; there is a fictionalised rendition by Michael Wray in 13 Ghost Stories from Lincolnshire (2003). Most of the above authors accept as fact Dunkerly’s testimony, if not the veracity of every part of ‘his’ account. Joanne Major’s blog post ‘The Murderous Tale Behind Tom Otter’s Lane’ (2015) is also very interesting on the subject, as is David Clark in It Happened in Lincolnshire (2016) – and Chris Hewis’s article, ‘Tom Otter: Fact or Folklore?’ (2013), mentioned above, which provides a very well-researched, authoritative summary. Anne Zouroudi’s story ‘Last Rites, or A Tale of Tom Otter’, in this project’s anthology Lincolnshire Folk Tales Reimagined (2025), speculates that Otter may have been framed, a notion on which she expands in her ‘Author’s Comment’ in the same volume.

Above: Gibbet Farm, marked on maps as Gibbet Lane Cottages. Note the styling on the sign.

Below: 1828 and 2024 Ordnance Survey maps for the same area, the earlier one clearly marked ‘Gibbet’. Bottom: detail from the current 1:25,000-scale map. Saxilby has grown very significantly, but much else remains essentially the same. On the 1885 map, Tom Otter’s Lane is labelled ‘Gibbet Lane’, though the gibbet had fallen down thirty-five years beforehand.

Words by RORY WATERMAN

Leave a comment