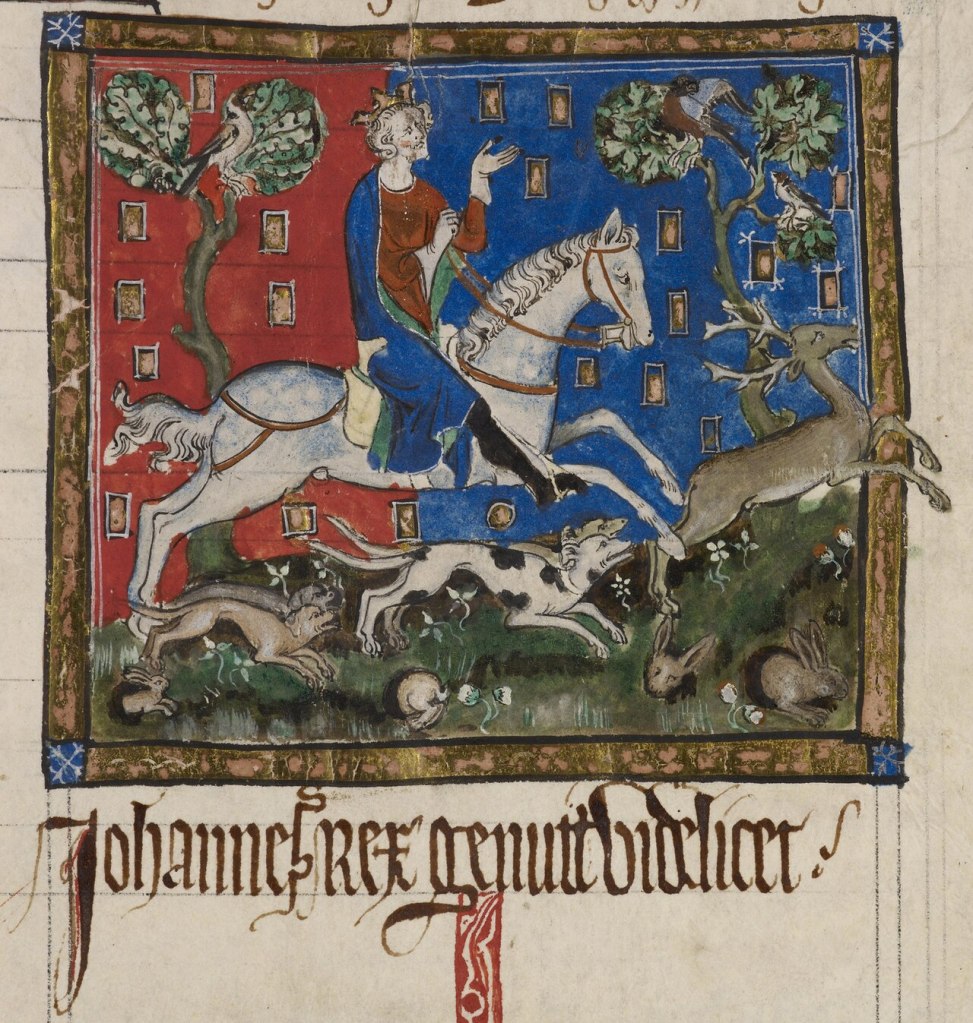

In 1216, a year after signing Magna Carta (a copy of which is on display in Lincoln Castle), King John was campaigning against rebel barons, who by then had amassed very considerable support from the French and the Scots. His route took him through Norfolk and on to Lincolnshire. It is said he sent his baggage ahead, via a more direct and treacherous route than the one he would take himself, and that all was lost in a tidal surge: men, horses, and wagons laden with equipment, clothing, relics, and jewels. This is believed to have occurred somewhere in the region of what is now Cross Keys Bridge, a swing bridge which used to carry trains and cars but now only serves the latter, across a canalised, straightened section of the River Nene through what is now (or for now) tamed, solid farmland. Roger of Wendover, a contemporary chronicler, gives the location as the River Wellester, but as this part of the country has been so artificially tamed in the past four centuries, nobody knows exactly where that was.

No trace of the jewels (if they were indeed lost), nor of anything else that was lost that day, has ever been found. Still, the legend persists, and some people still search for King John’s lost treasure. See, for example, this BBC article.

Swineshead Abbey, to the west and long-demolished (but close to Manwar Rings, which has a separate entry on our map and in this blog), is associated with another legend regarding King John. This is where he stayed after losing most of his worldly possessions, and before he travelled on to Newark where he would die. In Swineshead, John became ill with what historians think was probably dysentery. However, rumours soon arose that he had been poisoned by a monk at Swineshead, martyr to the cause, who drank from the same cup in order to convince the King it was safe to do so. This was reported in the late thirteenth century in the Brut Chronicle – though that was not written for an audience sympathetic to King John. Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland (1577) reinforced that probable myth, and Shakespeare used Holinshed’s Chronicles as his primary source for The Life and Death of King John, in which Hubert tells the Bastard that ‘The King, I fear, is poisoned by as monk’: ‘a resolvèd villain, / Whose bowels suddenly burst out.’

Words by RORY WATERMAN

Leave a comment